Interview with Sherwin Bitsui on Flood Song — February 11, 2010

Sherwin Bitsui is originally from White Cone, Arizona, on the Navajo Reservation. He is Diné of the Tódích’ii’nii (Bitter Water Clan), born for the Tłizíłaaní (Many Goats Clan). He holds an AFA from the Institute of American Indian Arts Creative Writing Program and a BFA from the University of Arizona in Tucson. He also works for literacy programs that bring poets and writers into public schools where there are Native American student populations. Bitsui has published his poems in American Poet, The Iowa Review, Frank (Paris), LIT, and elsewhere. His poems were also anthologized in Legitimate Dangers: American Poets of the New Century. His first book of poems, Shapeshift, was published by the University of Arizona Press in 2003.

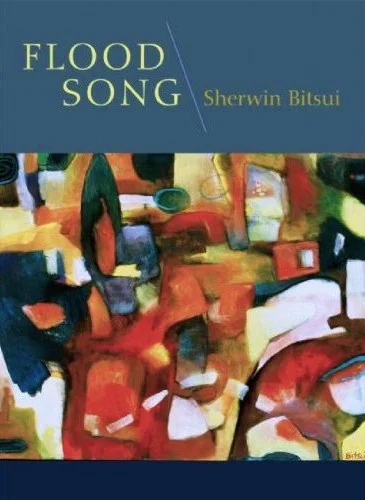

Christopher Nelson: First, let me say congratulations; Flood Song is a beautiful book, not only the poetry but the design and cover art, which is a painting of yours. I’m a painter who has come to favor the word over the brush, for my own expressions. Tell me about your visual art and its relation to your poetry.

Sherwin Bitsui: Over a decade ago when I was still living on Northern Arizona, I was given an acrylic paint set from a friend who saw some potential, I’m assuming, in my pursuit of visual art. I’m not a trained artist, but I took a liking to brushing paint onto canvas. At the time, I was, and still am, in love with the skies and landscape of my area that I grew up in. I wanted to capture some feeling of the place that I spent my early life in. When I attended the Institute of American Indian Arts, I started painting again. I was there as a creative writing major, and didn’t think that I was in any way worthy of showing my paintings to people. I did it because I liked the release it gave me. A fellow classmate who was a visual arts major walked by my dorm room once and saw a painting that I had just completed leaning against the wall. He expressed his interest in the piece. He was excited by what he saw and later showed up with a few large, blank canvases that he had stretched on recycled wood frames and told me to keep painting.

A year later, I entered a creative peak, which lasted for several months. It was also during this time that I wrote many of the poems that are now in Shapeshift. I took many photographs at this time as well. I wasn’t in a very good social space, often disheveled, and crazed by the need to express something beyond all I could express in words and image, and found myself in a place where the unspoken spoke loudest. I had stopped coming to class, hence one day my creative writing professor Jon Davis knocked on the door to my apartment after I’d been missing for a week. He found art work everywhere in my living room. Each piece I showed him was very much like showing him pages of a long poem that took on different incarnations. They were and still are a singular expression for me: the poems, the paintings and the photographs. They come from the same source.

Eventually, I used up all my creative energy and painted my last painting for the 20th century in that apartment at 4 a.m. one morning, basically having some sort of personal breakthrough. It was terrible, like an intense love that was leaving me, and I could not hold onto it anymore. The painting was an abstract/figurative piece (if there can be such a thing), its head, triangular, was tilted up, white shards were leaping out of its belly. Poetry remained afterwards. I think poetry was leaving that body and spilling to the floor to stay with me while the paintings moved onward, away from me.

Nelson: What thematic and stylistic concerns did you carry over from Shapeshift into Flood Song? Was there anything you deliberately did differently?

Bitsui: There weren’t many stylistic concerns on my part when I began writing Flood Song. I was aware that a poem was being birthed, and I knew somehow that this project would take several years to complete. I knew, perhaps mostly by intuition, that the poem would be complete when it felt “completed.” Shapeshift’s success gave me time to work on Flood Song in various corners of the continent and also afforded me audience during the reading tours that would hear this new poem. Their reactions were certainly necessary for the development of the book, but the most important detail is that I had time to create a piece that was largely a call-and-response between a poet and the poem. Eventually, I merged with the poem and the poem/song called out to audience, and they responded with excitement and anticipation for the new body of work.

Some of the poems in Shapeshift were written in a writing workshop, either at the Institute of American Indian Arts or the University of Arizona. Flood Song is, for the most part, written in parking lots, waiting rooms, airplane terminals, and in the early mornings when I couldn’t sleep. I carried drafts of it with me wherever I went and looked at it daily, obsessively.

Nelson: The book starts with dripping water, but very quickly the reader is swept into the flood. There’s a Whitman-like, image-rich rush to Flood Song. Is your creative process more like harnessing a wild horse or building an edifice brick by brick? I think of the Dionysian impulse of expression and the Apollonian impulse to order.

Bitsui: The Apollonian impulse to order probably occurs in the book’s revisions. The poems spilled forth in stages. There wasn’t a moment when the poem’s sections remained within any one house. They were always appearing in different parts of an invisible map, like sonar, and all I had to do was hold a bucket out and catch what few drops I could get. The process at times was much like attempting to control my dad’s roping horse during my childhood when I’d ride out alone to the valley behind the mesa north of our family’s settlement. The horse didn’t much see me as an authority figure and would hoof the dry earth thunderously, with his ears flicking crazily after several miles. Eventually, it broke for home and bolted back at high speed toward my family’s settlement. During these moments all I could do was release and trust that this horse knew what it was doing. It did, however, a few times, menacingly duck underneath low lying juniper branches, I believe, to scratch off some itchy spot of a young boy clinging onto its back for dear life.

Nelson: Flood Song has a lot of indigenous iconography juxtaposed with contemporary urban imagery: corn, drum, and bird wing paired with gasoline, television, and alarm clock. Is it overly dramatic to say that Flood Song is about surviving in the aftermath of the collision of two worlds?

Bitsui: The book is one collision in a long history of collisions. Certainly, as I get older, I’m more aware of how perspectives are shaped by environments. I am also aware of how I’ve been imprinted and/or mapped by my own cultural perspective, and how quickly that perspective has also changed in my lifetime. This experience is not solely my own, we all have to face such breakthroughs as living beings; I just happen to be going through this experience with a pen and/or laptop in hand. As a poet, I can only hope that I’m just writing poems that appear to witness such things.

The iconographies in the book all share a type of symbiotic relationship with each other. This activity is very much akin to the way I perceive the world to be. There isn’t much space for things to exist in secular environments. Everything is tunneling toward one big globular exposition, but even that destination is unknowable for now. It appears to me that the poem, as apparatus, adjusts such climates in its zone of sight to give the reader a more condensed sense of knowing, or an entrance to what knowledge is being revealed within its framing.

Nelson: Are you optimistic about the continuation of your cultural heritage?

Bitsui: Yes, quite so. At times I feel a sense of urgency to maintain it in its “traditional” form, but then I realize that what I view as traditional Navajo culture is somehow framed within an early twentieth-century context. The core of Navajo philosophy and culture continues to be practiced today in many communities on the Navajo Reservation. Our language is perhaps in danger of being lost with every new generation, but I feel there is a collective sense of awareness among many in my community that language is becoming increasingly important. In my family, the youth, beginning with the generation born in 80’s, are seemingly more communicative in English than in Navajo; though they understand the words and may have a base vocabulary, Navajo perhaps doesn’t seem to be as necessary because the majority of people within the family home are bilingual speakers.

I sometimes wonder if others in their generation have ever had one-on-one conversations with people like my ninety-year old paternal grandmother, who doesn’t speak any English at all. I’ve been lucky to have such moments with her. She gives me the local news when I go home, or asks about places I’ve traveled, new things that I might have seen. Lately, her stories are tinged with a kind of sadness, only because many people of her generation have and are passing on. Other times, I’m able to ask her about the history of my family, of how we came be in that corner of Dine’tah. She has an incredible sense of humor, and I love to tease her and see her smile.

As my generation moves forward, I hope we are able to honor the legacy of our grandparents and continue their stories for future generations. It is easy to Americanize one’s identity because it’s all around us all the time. It’s probably less easy to maintain a language—in any true form—that is slowly being replaced by another one, but I am hopeful that we’ll be able to create new opportunities for our language to continue to be practiced on a daily level and in all aspects of Navajo and North American Indigenous life. Personally, as a poet, I certainly could write more poems or stories in Navajo. It’s an obvious direction for me, and a way to see into new dimensions of Navajo worldview and thought. It will happen with time.

Nelson: “I map a shrinking map”—can this be taken as a sort of artist’s statement?

Bitsui: The vastness of place is certainly interrupted by the collisions of paradoxes, so I would probably say that it’s safe to render that line as an artistic statement for this book.